DayTap - A Privacy-First Daily Check-in App

I, like everyone else, have been using AI coding tools. I recently wrote about a toy web page I built to show how bad I am at sports gambling. For that project I used Lovable and Cursor for different pieces. By the time I was done, they already felt out of vogue. So I had to find a project to build with Claude Code. When I ran across an FT article about a viral Chinese app called “Are You Dead?”, I thought it was a perfect candidate. The app is dead simple. You click a button once a day, if you miss a day it sends a notification to your configured contact. I am personally not familiar with iOS development, but I am a software engineer with about 8 years of experience, so I thought I could put Claude Code to the test by building an iOS app similar to this one.

Some thoughts from a product lens

The core of the user experience is pretty simple. You add a couple contacts, you click a button, if you haven’t clicked a button in X time some type of notification is sent out. Where it gets interesting in my opinion is when you think about the types of users who may be interested in this app. There are quite a few possibilities:

- Antisocial solo dwellers

- Adults who are interested in keeping non-invasive tabs on their elderly parents or kids at college

- Those interested in a dead man’s switch.

I myself fall in the first camp and have thought if something happened to me in my apartment, someone may not realize for days. With that said, I thought it’d be most interesting to build a product for the third group. After all the goal of this was just to build something cool and get to know my way around Claude Code, not build the next big thing.

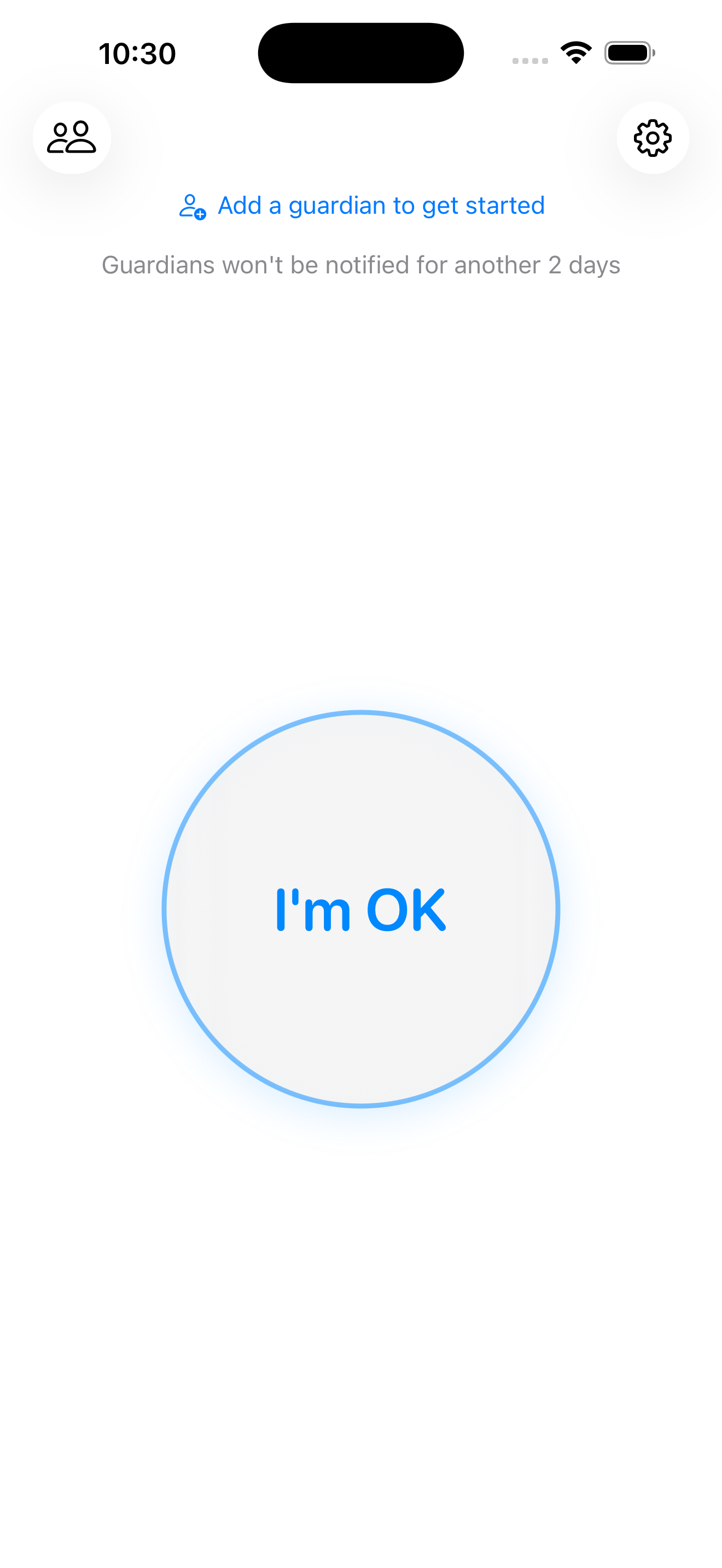

The result

I (or really Claude Code with Opus 4.5 and more recently Opus 4.6) built this iOS app with Swift. It features just the simple button to state you’re okay and has some CRUD actions like adding a “guardian” or a contact to be notified and updating your alert threshold.

I thought the implementation here was ok, but I don’t really know any better. One thing I found useful in my usage of Claude Code was to create a skill I called “product-team-review”. This would kick off a review from a number of subagents representing the roles on a product team. These included:

- Product Manager

- Product Designer

- Data Analyst

- User Researcher

- Tech Lead

- Test Automation Engineer

- Security Engineer After I added these reviews, I felt the feedback and subsequent code that was being implemented greatly improved. When the subagents focused on specific roles and responsibilities they caught so much more. They surfaced things I would have missed given my lack of familiarity with Swift, but framed them in a way that I could easily evaluate based on my experience in other domains.

Quick overview of the backend

In my experience with the AI tools they seem to really play well with serverless developer platforms. So that’s what I leveraged here.

┌─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ Serverless Edge Platform │

│ │

│ ┌────────────────┐ ┌──────────────────────┐ │

│ │ API Server │──────▶│ SQL Database │ │

│ │ - API routes │ │ PII encrypted │ │

│ │ - Auth │ │ at rest │ │

│ │ - Webhooks │ └──────────────────────┘ │

│ └───────┬────────┘ │

│ │ │

│ ┌───────▼────────────────────────────────────────┐ │

│ │ Asynchronous Workflows (4) │ │

│ │ │ │

│ │ AlertWorkflow Guardian notifications │ │

│ │ AllClearWorkflow Check-in: all-clear msg │ │

│ │ ReminderWorkflow Push notifications │ │

│ │ VerificationWorkflow New guardian → verify │ │

│ │ │ │

│ │ Automatic retries · state persistence │ │

│ └────────────────────────────────────────────────┘ │

│ │

└─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘

│ │ │ │

▼ ▼ ▼ ▼

┌────────┐ ┌────────┐ ┌────────┐ ┌──────────┐

│ Resend │ │ Twilio │ │ APNs │ │ Telegram │

│ Email │ │ SMS │ │ Push │ │ Bot API │

└────────┘ └────────┘ └────────┘ └──────────┘

There’s nothing too interesting here. Something I did do to try to accelerate this piece of the development was to create detailed GitHub issues for the tasks (with Claude’s help) then use another skill I created in Claude Code called “implement”. The implement skill would kick off just a simple workflow of 3 subagents to plan –> implement –> review/PR the change with human gates to approve the work after each step. Creating many git worktrees for the repo implementing many backend tasks in parallel really helped to speed things up.

Privacy & Security Concerns

This is where the architecture gets opinionated. Like I mentioned previously, I was interested in building for the “dead man’s switch” use case. Here my hypothetical users might live under an oppressive regime and the data DayTap stores might be very useful to them. Users that fall in this camp are (as we all should be) very cautious with their data and privacy. So I built with that as a first principle. DayTap is serious about privacy — it only stores what’s necessary, and makes it easy for user data to be deleted.

The MARCOM page does not use analytics (the iOS app has anonymized events via PostHog), only the latest check-in is kept, and all data is encrypted at rest.

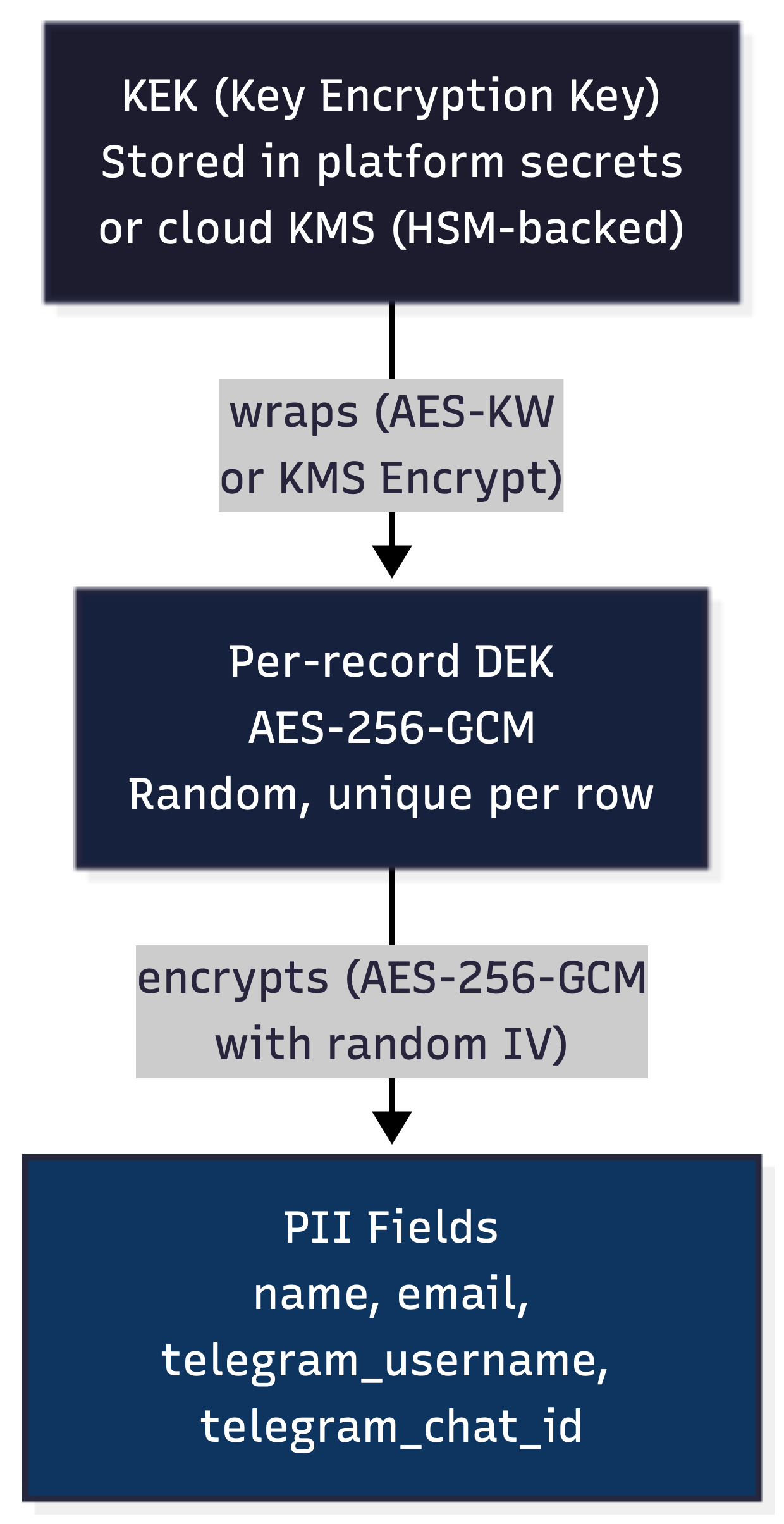

Envelope Encryption

Now most cloud providers’ default at rest encryption may help against someone stealing a physical hard drive from a data center, but it still has some weaknesses. There could be an insider with database access, a compromised backup, maybe a subpoena or government data request. To attempt to mitigate some of these things DayTap uses envelope encryption.

Every piece of PII is wrapped in its own Data Encryption Key (DEK) that is a random AES-256-GCM key. The DEK itself is then wrapped in a Key Encryption Key (KEK) and the DEK is stored alongside the PII. The KEK is stored in a cloud-based Key Management System (KMS) that is HSM-backed at a separate cloud provider than where the backend and DB live. This means the most realistic path to obtaining the plaintext data would require a compromise of the accounts at two separate cloud providers.

enrollee table:

┌──────────┬──────────────────────────────────┬──────────────────────────────────┐

│ id │ name │ wrapped_dek │

├──────────┼──────────────────────────────────┼──────────────────────────────────┤

│ uuid-1 │ aGVsbG8gd29ybGQ=... (encrypted) │ kms:CiQA3v7... (KMS-wrapped) │

│ uuid-2 │ Zm9vIGJhcg==... (encrypted) │ kms:DiRA4w8... (KMS-wrapped) │

└──────────┴──────────────────────────────────┴──────────────────────────────────┘

Blind Indexes

When you encrypt sensitive data like phone numbers and email addresses at rest, you lose the ability to query it. You can’t ask the database “find the user with email [email protected]” if that email is encrypted with a unique key. Decrypting every row to check would be slow and expensive. To solve for this DayTap uses blind indexes.

Simple blind index implementation

To start, let’s cover a simple and more straightforward blind index implementation then cover what is done at DayTap. Blind indexes create a one-way deterministic fingerprint of the plaintext data. A simple implementation may use HMAC-SHA256 — the HMAC hash is stored alongside the encrypted value. This ensures typical business logic like not allowing duplicate user emails can be preserved even when all of our data is encrypted at rest.

┌─────────────────────────────────────┐

Email │ Database Row │

"[email protected]" │ │

│ │ email: AES-256-GCM(...) │

│ │ (encrypted, unreadable) │

├───► AES-GCM ──┼──────────────────────────────► │

│ encrypt │ │

│ │ email_hash: a7c3f9... │

└───► HMAC ──────┼──────────────────────────────► │

SHA-256 │ (blind index, searchable) │

└─────────────────────────────────────┘

── Later: "Which user has email [email protected]?" ──

Incoming: "[email protected]"

│

└───► HMAC ──────► a7c3f9...

SHA-256

│

SELECT * FROM enrollee

WHERE email_hash = 'a7c3f9...'

│

┌────▼────┐

│ Match! │ ──► Decrypt email

└─────────┘ with record's DEK

This HMAC key can only be used to produce hashes, not decrypt any actual data. To me, this still felt like the weak point of the system. Hypothetically, if the database and the HMAC key itself were compromised, a threat actor could perform a dictionary attack where they tried to hash many emails or names using the compromised HMAC key until they produced hashes that matched the values found in the database. With HMAC-SHA256, this would be a relatively trivial exercise. This is the same reason security experts recommend algorithms like Argon2 for password hashing — they make brute-force attacks orders of magnitude more expensive.

How blind indexes work at DayTap

Main Service Argon2 Service

─────────── ──────────────────────────────

Holds: HMAC_KEY Holds: PEPPER

Email: "[email protected]"

│

├───► AES-GCM encrypt ──────► Stored as encrypted email

│ (unreadable at rest)

│

└───► HMAC-SHA256 ──────────► Argon2id(hmac_output, PEPPER)

(keyed intermediate) │

▼

Final index: b84e1c...

│

▼

Truncated to: b84e...

│

▼

Stored as email_hash

(searchable, ambiguous)

── Later: "Which user has email [email protected]?" ──

Incoming: "[email protected]"

│

└───► HMAC-SHA256 ──────────► Argon2id(hmac_output, PEPPER)

│

▼

b84e...

(truncated index)

│

SELECT * FROM enrollee

WHERE email_hash = 'b84e...'

│

┌───────▼───────┐

│ Bucket of │

│ candidates │──► Decrypt each,

│ (1-5 rows) │ find exact match

└───────────────┘

The blind index computation for DayTap leverages a few practices to provide some defense in depth. To start, the blind index computation is split across two independent services.

- The main serverless function applies HMAC-SHA256 using its own secret key, producing a keyed intermediate value

- That intermediate is sent to a separate Argon2 serverless function, which applies Argon2id with its own secret pepper to produce the final blind index

The main serverless function never sends plaintext to the Argon2 serverless function — only the HMAC output. Neither service alone can compute the full index. This architecture provides the following benefits:

Slow hashing — Argon2id is intentionally expensive to compute. Unlike HMAC-SHA256 which can process billions of hashes per second, Argon2id limits an attacker to thousands, turning a minutes-long dictionary attack into one that takes months or years.

Memory hardness — Argon2id requires significant memory per computation, making GPU-based parallelization more impractical. An attacker can’t simply throw more hardware at the problem the way they can with CPU-only hash functions.

Split trust — The blind index computation is split across two independent services with separate secrets. Compromising the main serverless function’s HMAC key isn’t enough — the attacker still needs the Argon2 function’s pepper. Compromising the Argon2 function isn’t enough either — it never sees plaintext, only HMAC output. An attacker would need to compromise both services and the database simultaneously.

Next, after obtaining this hash, rather than storing the full hash, we only store a prefix of the blind index. This means our business logic could return a small number of candidate rows we decrypt instead of a single row in the simple implementation. From an attacker’s perspective, even if they manage to brute-force the hash computation, each truncated index maps to multiple possible plaintext values — they can’t definitively determine which record belongs to which input.

Final thoughts on Privacy and Security

Is all of this overkill? Probably. Does it make the app slower? Definitely. Like I mentioned, though, I wanted to build with security as a first principle. Everything took a backseat to that, including performance.

This is honestly the area where I enjoyed Claude Code the most. It was nice having it just implement the whole iOS app, but implementing a feature like this may have been a bit prohibitively time-consuming in personal projects before and is now much easier. As I tinker with the app for fun moving forward, this is where I want to go deeper. Having Claude be a tutor to help inform me on what security solutions are out there is exactly what I’m looking for. These are not solutions Claude came up with out of the box — it took more of a back-and-forth and I had to continuously challenge Claude to come up with a better solution.

I felt I grew the most as an engineer with Claude during this process. I am not really any better at iOS development today than I was yesterday. I could not whip up an iOS app in a short amount of time without AI help today. I do feel like I have some applicable learnings from exploring different solutions for user privacy and security with Claude that I can leverage down the road.

Wrapping up

The AI tools are really improving rapidly and even though I was skeptical this time last year, I am all in on them now. I have been too afraid to run what is now OpenClaw, but every day it feels like things take another leap forward.

If you’re interested in checking out DayTap, the web-based landing page is here and a direct link to the iOS app is here. I’m going to continue to tinker on DayTap for some time. The plan is to build out some more features, double down on security and privacy a bit more, and maybe get an Android version going.

Now let me leave with a couple of complaints I want to throw out to the internet ether.

- I honestly feel like Opus 4.5 was better than Opus 4.6 at coding. I get frustrated with Opus 4.6 way more regularly, but I can’t find anyone on the internet that feels the same.

- DayTap was banned in China for being a dead man’s switch app. What I don’t get is that it’s similar to a Chinese app referenced in the intro — why was that one not banned?